Curiosity as the ultimate arbiter

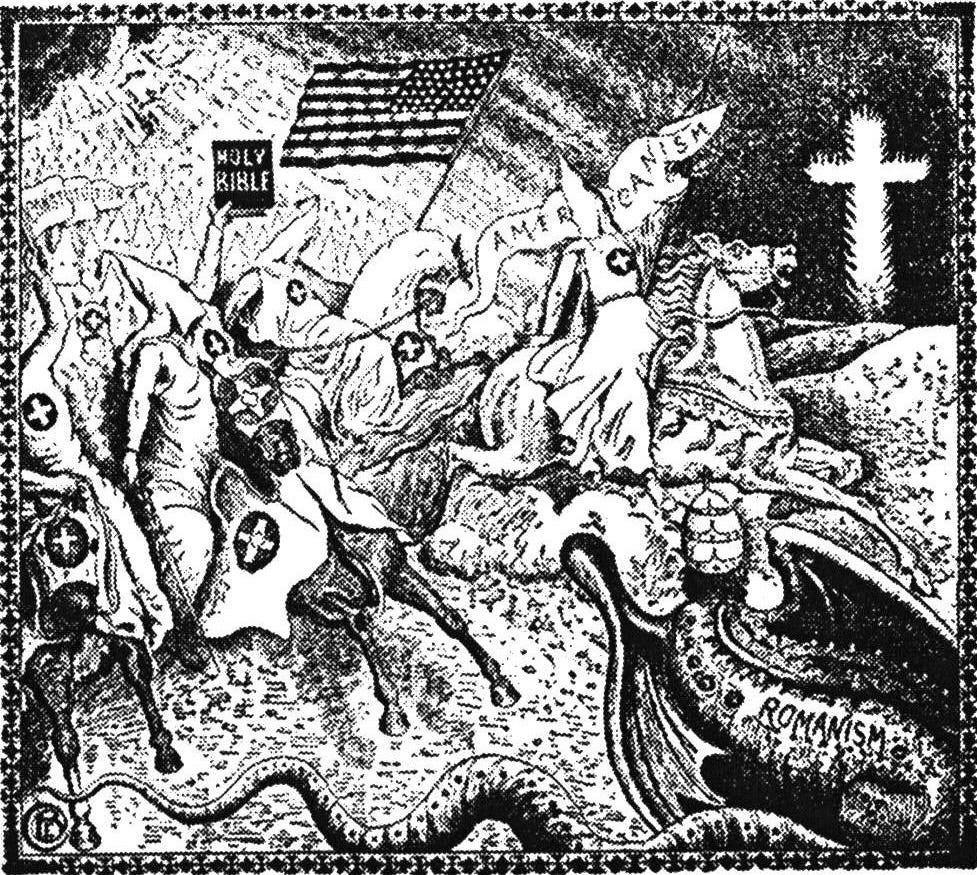

Daryl Davis' attempt to understand the KKK's hate for people like him

One summer day, nearly a decade ago, while I was sitting at a stop light in my Toyota Prius — windows down, waiting for the left turn arrow — a man in an approaching car hollered out his window as he passed by: “Why don’t you buy American made next time, asshole!”

A little bewildered (as this was a first for me), my husband assured me his insult was indeed directed at us. We both had a good laugh, joked about how it was more likely that my car was made in America than his and moved on to another topic.

But with the incident still lingering in my mind, I began to seethe. This man, who knew nothing about me other than the fact that I owned a Prius judged me based on that one fact alone. He knew nothing of the fact that I had to commute two hours every day to work and spent a fifth of my salary on gas — notwithstanding the fact that my salary was below the poverty line at that time.

How dare he … fucker.

But perhaps more than that, I was bothered by the fact that I was bothered. Why did I care so much what this man thought? Who was he anyways? He was no one to me; I likely would never see him again (or even recognize him if I did). His remark and insult had no bearing on my life, and yet I allowed his words to take hold of me, filling me with momentary rage.

Of course, it wasn’t the first and wouldn’t be the last time something like this happened.

Afterall, the desire to be understood and judged for who we truly are is a powerful and natural one. And when someone makes no attempt to do so, anger, too, is a natural reaction.

But emotions, though natural and easy, aren’t known for being the best guide. They’re messy and fallible, often result in rash decision-making and rarely lead to progress.

The more difficult thing to do is to react with curiosity — something Daryl Davis knows a little about.

It was the music that brought us together.

As a young blues musician, Daryl Davis was accustomed to hopping from bar to bar, playing in various bands. But one night in 1983, after performing in a country band at the Silver Dollar Lounge in Frederick, Maryland, he experienced something entirely new.

An older man approached him to compliment his playing.

“I thanked him, shook his hand and he says, ‘You know this is the first time I ever heard a black man play piano like Jerry Lee Lewis,’” Davis later told NPR.

Surprised that the man had no knowledge of the black blues and “boogie woogie” origins of Lewis’ music, Davis enlightened him. And although the man didn’t believe him, he invited Davis to join him for a drink — admittedly a first for the man. “He says, ‘You know, this is the first time I ever sat down and had a drink with a black man?’” Davis said.

The man, it turned out, was a card-carrying member of the Ku Klux Klan (even showing Davis his card to prove it). Before they parted ways, the man gave Davis his number, telling him to call him any time he was playing that bar.

“It was the music that brought us together,” Davis said. “That was a seed planted. So what do you do when you plant a seed? You nourish it.”

Davis called the man every time he played that bar, eventually asking him if he would introduce him to other Klan members. Soon Davis began traveling the country, meeting with KKK leaders and members seeking an answer to the question: “How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?”

Armed with vast knowledge about the KKK, he met with hundreds of Klansmen to have an honest conversation and to try to understand them.

“That began to chip away at their ideology because when two enemies are talking, they’re not fighting,” Davis said. “It’s when the talking ceases that the ground becomes fertile for violence.”

Taking place over the span of 40-plus years, these meetings ultimately led over 200 Klansmen to leave the KKK, many of them giving their robes and hoods to Davis to keep.

“If you spend five minutes with your worst enemy … you will find that you both have something in common,” Davis said. “As you build upon those commonalities, you’re forming a relationship and as you build that relationship, you’re forming a friendship. That’s what would happen. I didn’t convert anybody. They saw the light and converted themselves.”

Read more about Daryl Davis’ experience here.